As far as we know, Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches, is unique in 17th-century English painting due to the way it depicts a Black woman and its direct discussion of the perceived vanity of cosmetics.

Dated to c.1655, the painting was made during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, only a few years after English society had been turned upside-down with the execution of Charles I and abolition of the monarchy in 1649.

It offers a new lens from which to study how race, gender, morality and identity were understood during one of the tumultuous times in English history.

Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches is an extremely unusual depiction of a Black and a white woman for this period. Most paintings which include Black and white sitters in the 17th and 18th centuries make the inequality between the individuals stark.

In Pierre Mignard the Elder’s Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth with an unknown female attendant, 1682, (National Portrait Gallery) and Peter Lely’s Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemache, Later Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale with a Black Servant, c.1651, (Ham House, National Trust), the white aristocratic sitter is the focal point of the painting, taking up the majority of the composition and wearing billowing, colourful silks.

The Black sitters, most likely enslaved attendants, are portrayed as diminutive in comparison, looking away from the viewer and up into the face of the white sitter.

Although the identity of the Black sitters in these paintings is currently unknown, it is likely they were real people. The artist, however, has chosen to depict them as property, as allusions to the white sitter’s wealth and power.

Both Lely and Mignard associate the Black sitters with accessories that make them appear ‘exotic’: pearls, coral and seashells; they are reduced to being another symbol of luxury. (See Marjorie H. Morgan and Janet Couloute discuss the depiction of race in British portraiture through their writings on Art UK). It is only recently that museums have even begun referring to there being two sitters within portraits such as these, with historic titles only referencing the existence of a white sitter.

In Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches, the women take up an equal space within the composition and mirror each other’s fashions. However, this is not a depiction of equality but rather a troubling image of the racism and misogyny that was rampant during the 17th century.

This painting is not a portrait but rather a morality painting, which condemns women for the sin of vanity. Across the top of the canvas, the inscription reads:

I black with white bespott: y[o]u white w[i]th blacke this Evill / proceeds from thy proud hart, then take her: Devill.

Both women are condemned for their use of cosmetic patches, but the artist particularly criticises the white woman. Written as if from the perspective of the Black woman, the inscription encourages the devil to drag the white woman to hell for her sins.

Cosmetic patches were made of small pieces of silk, satin or leather cut into a shape and glued onto the face. Circles were popular but other shapes were also used, such as stars or moons. Some of the patches in this painting are even more intricate. Here they could have an astrological significance, perhaps even linked to witchcraft, but this requires further research. Patches were worn for a number of reasons, including to cover scars or blemishes.

Here, the implication is that cosmetics are a sign of pride and vanity which will cause the user to be punished. The white woman is not just wearing patches but also seems to be wearing makeup, a form of blush and lipstick as well as white face powder or paint (ceruse). This is particularly evident around the eyes, where it seems to be cracking.

Here, as far as we understand it so far, the Black woman’s presence is intended to emphasise the white woman’s sins. Patches were criticized by many in prints and books as a foreign practice that changed one’s ‘God-given’ features. John Bulwer’s book Anthrometamorphosis, 1653, and its appendix The English Gallant, traced the fashion for patches to the customs of peoples from other parts of the world. In this book, which catalogues different methods of body modification around the world, he states:

Painting and Black patches are notoriously known to have been the primitive inventions of the barbarous Painter-stainers of India.

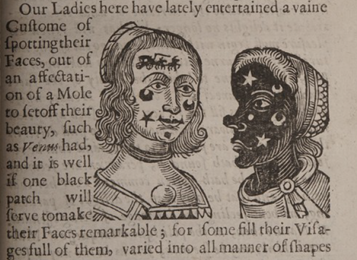

Bulwer’s treatise includes the same illustration twice, of a Black woman and a white woman wearing elaborate cosmetic patches. It bears a remarkable similarity to Compton Verney’s painting, although it is unclear which came first.

Detail from John Bulwer, Anthropometamorphosis, man transformed,1653

It seems, therefore, that the Black woman’s presence in Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches is supposed to suggest that the white woman’s use of cosmetic patches is not just vain, but associates her with non-European peoples and customs, ‘undermining’ her national identity. It is the equality between these two figures which the artist considers to be dangerous, rather than something to be celebrated.

Whilst the painting is unusual, there are certain differences between the figures that we can trace back to the portrait conventions followed by artists like Lely and Mignard.

Whilst both women wear fashionably cut dresses and pearl necklaces, the Black woman alone wears a pearl earring, and her dress is not of pink silk but is rather striped. Both the striped garment and earring correspond with traditional depictions of Black people in portraiture at this time, indicating their ‘otherness’ and aligning them colonial wealth and the ‘exotic’.

Whilst the painting does rely on certain portraiture conventions, the inscription places this painting firmly within the category of morality painting and genre painting. These women are ‘types’ rather than individuals. The way the women mirror each other removes any sense of individuality, as does the stylised way in which they are painted.

Apart from acting as a warning to the viewer, we do not yet know the purpose of Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches. We believe that the painting was either bought or commissioned by the Kenyon family, a gentry family residing in Lancashire.

It remained in the possession of their descendants until it went to auction in 2021. The family had moved from Lancashire to Shropshire in the 19th century and, therefore, we do not know how or where the painting was originally displayed.

There is potentially another painting which might be connected to Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches.

In 1949, Lord Kenyon wrote a letter which was published in Country Life magazine asking for assistance in understanding the unusual painting in his possession. In response, Lord Leigh, of Stoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire, replied describing a similar painting in his collection. This work, the whereabouts of which are currently unknown, seems to similarly condemn vanity, depicting a skeleton holding an arrow above the heart of a white woman wearing patches. It bears a similar inscription:

Repent; Tomorrow; Tomorrow Madam is another day, It is none of yours. You must to night away.

Image from Country Life, November 11, 1949, © Country Life Magazine

This painting raises the possibility that Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches might have formed part of a series of morality paintings.

The painting travelled to the Yale Centre for British Art (YCBA) in 2024 for research, conservation and technical analysis. This revealed a possible artist for the painting, but ultimately, more research is needed, and the work remains attributed to an unknown artist.

The Kenyon family were part of a community of Catholic families based in Lancashire. This raises the possibility of a connection with the artist Jerome Hesketh, a portrait painter and, perhaps more importantly, a Jesuit priest, operating in the same remote area of the country.

You can find out about the YCBA’s technical analysis of the painting and their research into Hesketh by watching the video on this webpage.

Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches reveals how visual culture was used to regain a sense of control during a time of national upheaval through the oppression of women and those viewed as outsiders due to their race or nationality. Research is still ongoing into the painting, its historical significance and the artist who made it and there is much still to discover.

Compton Verney would like to thank the Yale Centre for British Art for their research into and conservation of Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches, c.1655. In particular, we would like to extend our thanks to Dr Edward Town, Assistant Curator of Paintings and Sculpture; Dr Jemma Field, Associate Director of Research; and Jessica David, Senior Conservator of Paintings. Their research underpins much of this essay.